Office Skills The skills needed in your work as a paralegal, i.e. source analysis, critical reading and writing and digital know-how, are useful for any career. These office skills, essential for paralegal work, offer a promising outlook for climbing the ladder as a leading paralegal. However,

Today, the New York Times’ District Court is facing a lawsuit against OpenAI and Microsoft, the creators of the GPT language model and ChatGPT, which, just over a year ago, pulled the trigger of the artificial intelligence revolution. In the lawsuit, the most famous media in the world accuses the company of copyright infringement, and requires, among other things, damages of “billions of dollars”.

The lawsuit was based on the allegation that the creators of the GPT used materials belonging to the NYT to learn the language model without permission. And, emphasizes the lawsuit, in the amount of training data were hundreds of thousands of articles, which, in the process of learning the model, was given additional weight.

At first, when I read the news of such a lawsuit, I thought that using NYT articles to teach the GPT model was an unproven charge that could be the subject of litigation. But, reading the text of the lawsuit, I realized that the newspaper presents rather strong evidence, and it is not clear whether the defendants will ever contest the presence of the plaintiff’s materials in their training data. For example, the lawsuit results in a dialogue in which ChatGPT quotes word for word one specific article published by a newspaper. It is also mentioned that in the databases used for the training of early GPT articles from the newspaper’s website became part of a special archive of “high quality materials”, which was given more weight during the training.

The New York Times demands not only compensation (its size is not specified, but we are talking about billions), but also wants to achieve the destruction of all models that were trained, including the newspaper articles, and ban such training in the future.

This is not the first case of its kind: over the past year, several authors and copyright holders have already sued various creators of “artificial intelligence” models, accusing them of unlicensed use of their intellectual property to teach their products. The lawsuits were not only about texts, but also about music and photos!

It is important to understand that the law gives rights holders control over who can make copies of their works. As a New York Times subscriber, I have the right to read their articles, but I can only reproduce them in their entirety with the permission of the newspaper’s owners. (There is a small loophole: limited citation is legally considered acceptable use.)

However, I can absolutely use the knowledge gained from reading the New York Times as I please. I can write a post based on them on my blog – the main thing is not to copy the entire text of the article.

And there’s a question that doesn’t have a definite answer yet: Is training a data model, is it a legally protected copy, or is it permissible learning? After all, when I read and memorize an article, I keep in my head its essence and not the exact text, while the language models absorb into themselves the specific order of words (this is their basic principle!)

And if someone fed the model many works by one author, then you can ask the intellect to “paint a picture in the style of Dali”, “poems in the style of Mayakovsky” or “generate a song like Taylor Swift”.

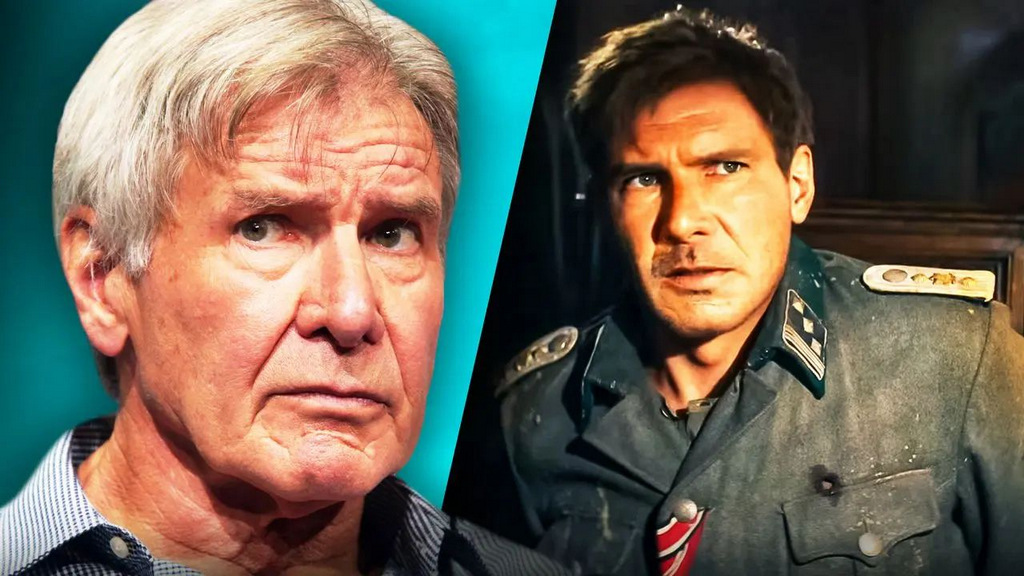

On the one hand, the parody is protected by law, and on the other hand, there is already a well-established opinion that if you want to use young Garison Ford in your new film, drawn using computer graphics, you can not do it without the permission of Mr Ford himself. And even in the case of dead actors, we have to negotiate with their heirs.

So far, there is no single answer – at least, I find this question rather difficult. I am sure that there are strong supporters of both options among the readers of the blog. But even if one of us can resolve this dispute with full confidence in favor of journalists or IT specialists, the courts will decide here.

Almost everyone is confident that in the near future this issue will be presented in some form before the Supreme Court of the United States. After all, what could be better than entrusting such twenty-first century legal nuances to nine mid-to-late-aged judges.